Mother was dying. Asked my sister courteously

(what other way can you think?) – troubled, as one

who’d forgotten a little something—

“Martha, could you tell me who my husband was?”

Then she heard the news. Her gentle cheeks trembled

with a gust of fear – or amazement, out of years past.

–“Not one of those terrible Glazes from Elkton!”

Her people were (and are to this day)

a pleasant, loving, ceremonious folk

who number cousins down through the generations,

build their houses slowly, one next to another,

as children run in and out like spinning bobbins,

weaving the cloth of coming and going and having gone.

My father’s clan were a mad cannibalistic lot.

His father, a run-away, spent the civil war

in the saddle, cutting and bandaging Forrest’s men,

hadn’t spoken to his father or hated step-mother

in years – later, didn’t speak to his second wife–

all the time they were raising a clever brood of five.

Descended from such a union, it’s not prodigy

that I crawl like a baffled planet across an eerie sky.

Driven first by bitter attachment to blood,

nothing at all to do with either sense or the time,

whether my people care for my cares or what I do,

and also, without a break in the music, lives out of step

wildly alone, balks at their company

or being away from it, either remembered or alone.

Yet I’ve had luck. That I could not destroy myself as my father did,

and had one talisman to clutch, and lonely craft

woven out of her music, his passion for words–

her calm plenitude, his untamed wildness,

which by its spell delivers me across ditches,

flares in darkness. By its strange gift to shuttle

madness and wrong, it weaves fire and water

into a strong cloth spun out of one house

winding into another, up against sky, down into earth,

strapping filth and nakedness into song.

© Andrew Glaze Estate, 2018, previously unpublished.

The story at the beginning of the poem is completely genuine, and has become legendary among the members of the Glaze family.

My Grandmother, Mildred Ezell Glaze, died just short of turning 94 years old, in 1981. The average age of death in her family was always over 90. Her one downfall was osteoporosis which landed her in the hospital, with a broken hip – twice. I remember that both times her doctors predicted she’d leave us soon from congestive heart failure after becoming bedridden, only to eat their words — twice. It was only after she tried to open a window and her back collapsed that she really did begin to slide downhill, at which point her memory decided to join in for the ride.

She had always been a petit but firm matriarchal figure. Her white hair behaved itself in a tidy French twist during the day, but cascaded down her back when she brushed it at night. She was from Pulaski Tennessee, outside of Nashville. It was a metropolis compared to Elkton just down the road.

As a teen, during a visit to Birmingham with my father, I went along to a dinner party one of her friends was hosting. Afterwards, Mamma sat in a chat circle with her friends and I realized that every one of them had blue eyes and a pearl necklace.

My father liked to repeat a story she’d told him about a similar gathering many years earlier. It was spring, and one of her friends had invited the rest of them to her home at the height of strawberry season. They all dressed in their best and sat around her oval dining table, chatting and eating as they dipped their strawberries into a large platter of white powdered sugar at the center of the table.

It was during this idyllic scene of privileged indulgence that the hostess’s pet parrot suddenly got the notion to fly into the room in search of his mistress and aimed for a landing spot. He selected the dining table. It was only as he began his descent that he noticed the platter of powdered sugar below him and changed his mind. Pumping his wings furiously to regain height, a giant mushroom cloud of powdered sugar arose all around him and female guests ran in every direction. When the dust settled everyone was coated in white.

“Mamma”, as I called her (for Grandma), had 5 sisters and 2 brothers. They grew up living near their cousins and did indeed spend the day running between houses. She had a wonderfully happy childhood. For their entire lives the 5 girls went by the names their youngest sister Mary gave them as a baby. Martha was “Arter”, Marjorie was “Argie”, Mildred was “Mimmi”, and Sarah was “Tarai”.

My mother once told me that Mamma, who was her mother-in-law at the time, had confided, “Andy’s so proud that he resembles his father that I never had the heart to tell him that he looks just like my own father. I married a man who looked like my father.”

The reality was that he also inherited many of the personality traits and interests of her father. His own father wanted a son to play catch with, and took him to shoot guns at the driving range, but he was more interested in watching baseball, reading, and listening to classical music. According to my father, his younger sister was the apple of their dad’s eye. His mother realized this, and later admitted that she made a conscious effort to be my father’s champion to try and balance things out. It helped, but not completely. He always struggled under the feeling that he never quite lived up to his father’s expectations, and since my grandfather died when my father was 25 and overseas in the army, he was left to try and wrestle it out through his poems.

Ironically, when my brother became a teenager he spent most of his free time playing softball in Central Park, dreamt of going to the pros, and once lamented to me that our father was never the type to take him out and throw a ball around with him. Clearly, it skipped a generation. As for myself, my father cultivated a large number of common interests in me, which is how I ended up excitedly attending my first opera with him when I was all of four years old, and attending Gilbert & Sullivan productions with him as a tween. At age 8 I loved nothing more than to watch the “Play of the Week” on television with my parents. On the other hand, my brother inherited our father’s gentle and shy personality, enormous loyalty to the women in his life, quick witted sense of humor, and the ability to generate nonstop groan worthy puns. The talent for puns was an ability that my father also shared with his former father-in-law, W.Y. Elliott, and even, to my great dismay, with my husband. As puns have never been my favorite form of humor, I have spent my life cringing my way through many family dinners.

My father spoke several times to me about the fact that his mother read “Water Babies” to him as a child and he remembered it as a beautiful tale. So much so that he picked it up years later to reread, only to discover that it contained a large amount of religious content that he had no memory of. So he asked his mother about it and she replied, “Oh, I left all that stuff out when I read it to you”. He was impressed by her ability to edit on the fly. He carried on the family tradition of reading books to the younger generation at bedtime. By the time I left to study in England shortly before turning 19, he’d carried on reading to me through high school until we finished the entire Hobbit and Lord of the Rings series. I did the same with my daughter and she was in high school by the time we finished the 7th book of the Harry Potter series. My brother not only read to his children but shared our father’s interest in reading P.G. Wodehouse books aloud to his wife in the evening.

After the divorce, which was initiated by my mother, I remember visiting Mamma’s apartment the following summer and noticing that she’d carefully cut my mother out of a framed group photo. According to my uncle, she also massacred the entire photo album. There was no mistaking it; she was pissed off. Despite his great emotional pain, our father never said a word to us against our mother. His loyalty remained unshaken, and he remained friends with our mother’s parents. Mamma also remained congenial to them after the divorce and told me she’d visited the local funeral parlor to sign the condolence book when our maternal grandmother died. It was a lovely gesture that had required effort. She had no way to get there other than to call a taxi.

Mamma had travelled to some extent when she was younger, and she visited us in New York City on several occasions as she grew older. These trips gave me the opportunity to observe a skill that my father and my uncle had discussed with bemused amazement for many years. Mamma had the ability to strike up a conversation with a total stranger in any city, and immediately find some direct connection they had to Pulaski Tennessee. It happened repeatedly. In Mamma’s world, all roads led to Pulaski.

Before she died I asked her to leave me a statuette that I’d always admired sitting on her living room shelf. My father was thrilled that she fulfilled my request, because he loved it too. The statuette had a story to accompany it. She said that my grandfather had stopped off to visit a friend who had an art gallery, and fell in love with the statuette. So he bought it. He bought it even though it was during WW2 and he had to use all of the food ration stamps they had for the entire month, which he happened to have with him since he had just picked them up. She said she was ready to kill him at the time, but was glad to have the statuette now. Personally, I think our grandfather realized that he had other options available to him and that they’d never starve to death. You see, a few years earlier Mamma had presented me with an Elgin watch she had as a spare, explaining that it was one that Dr. Glaze had received as a barter payment from a patient. He was a dermatologist, and I’m going to hazard a guess that his patients often paid him with food and ration stamps as well.

This may sound strange, but my grandmother’s teeth outlived her. When she eventually landed in a nursing home, every evening a new nurse would ask her for her dentures, and Mamma would reply, “They’re my own”. And every evening they wouldn’t believe her until they finally read her chart and realized that, at age 93, she did indeed still have all of her own teeth. In addition, her teeth had few, if any, fillings. My father inherited her teeth genetics. He used to come home from dental cleanings and tell us that while he was sitting in the examination chair, the dentist had dragged every single member of his staff into the room exclaiming, “Look at this set of teeth, because you’ll never see another set like them again!!!” Her Ezell family DNA for teeth is what everyone in our family hopes to inherit. My brother was lucky enough to be on the receiving end. It might seem like a strange sort of legacy to leave behind, and it’s about as predictable as a winning lottery ticket, but to those in the family who have it, it’s priceless!

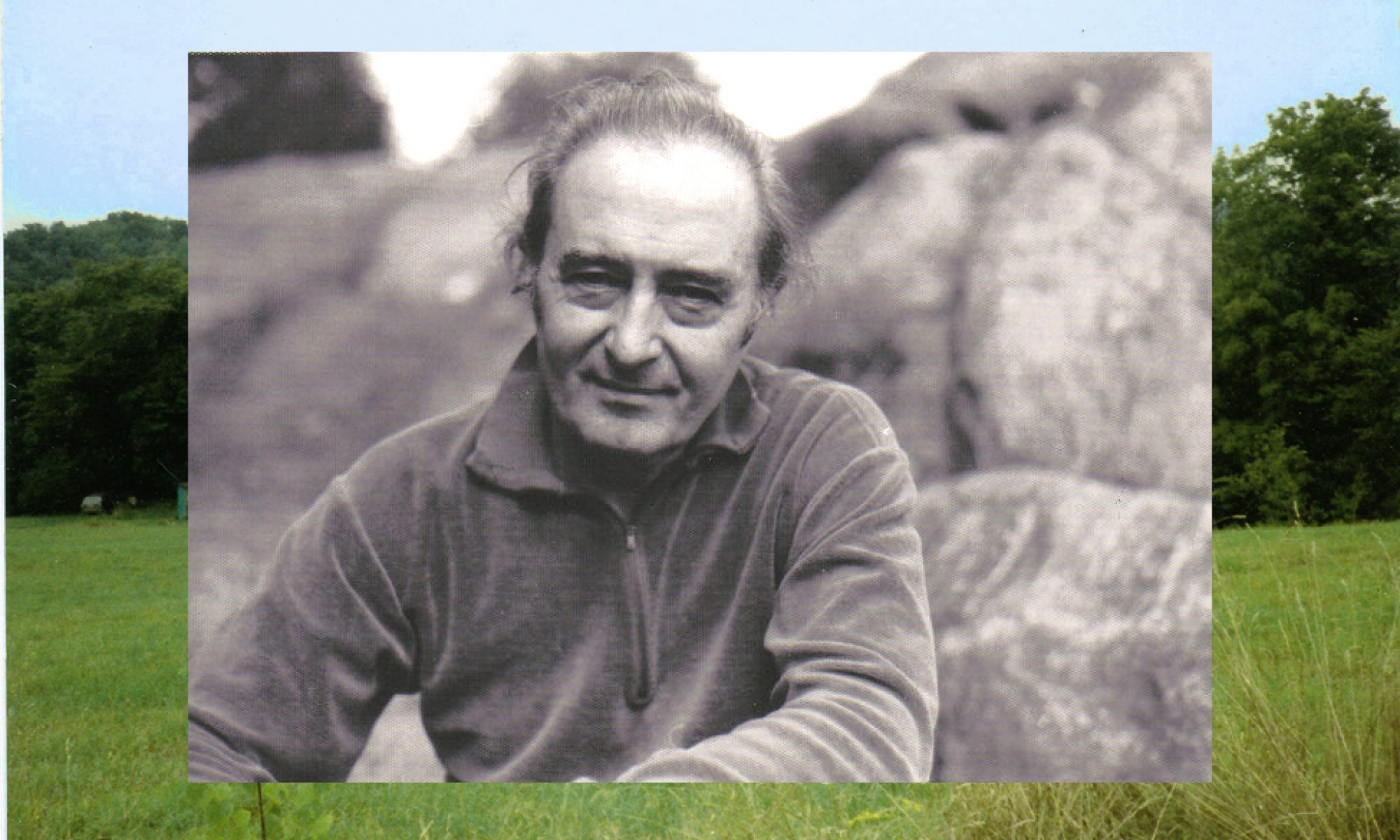

Mildred Ezell Glaze, photographed by Andrew Glaze, 1938.

Property of the Andrew Glaze Estate, 2018

— E. Glaze

Nice post thannks for sharing

LikeLike