In memory of Adele de la Barre Robinson

It was a strange wood in which she decided

to consider herself lost.

It was filled with sun at cool angles,

Sylvanum densiflora, bracken,

live trees with lulling voices.

Trunks of bodies starting from the earth like plants.

Screams without throats,

Lianas tangled in unnamable wildness—

a world which would not accept order.

Existence snuffled with warty nozzle about this stranger

unacquainted with mere fact,

but who did not evade its vilest bubblings and quakings.

She would not draw back from the black crevasses,

which allowed her to name it a name,

imagine it to a shape it had not become

except as a neighbor to fear.

She recollected a prophet who spoke from a tree.

At first doubtfully, then gratefully, at last

brimming with courage, became what

was determined to take her,

and turning it inside out,

grew herself into death and gave it her soul.

© Andrew Glaze 2015, from Overheard In A Drugstore

Adele Robinson, as my father referred to her, was a highly unusual female. In 1960’s Birmingham, Alabama, she began publishing a series of small press literary magazines, using her degree in Design and interest in writing and editing. The goal was to cultivate the careers of poets and writers that she believed in, and my father was fortunate enough to become a favorite in her start-up.

In 1963 her pioneer effort, a booklet titled The TOKEN, landed on my lap when my father tossed it from the doorway as he muttered, “I have poems in it” and headed off to eat lunch. It had just arrived in the mail. This was actually a pivotal moment in our relationship. Before then, I’d never realized that my father wrote poems that people actually published much less read any of them. Even more significant, this publication contained a poem about ME. I immediately became a lifelong fan at the age of twelve. (In 1991, after tweaking the poem to his satisfaction, “To Betsy” re-appeared in Reality Street, his fifth book ).

According to my research, Adele Sophie De La Barre was a descendant of a French founding family of New Orleans which still lays claim to an ancestral mansion in that city. She herself was born in White Castle, LA in 1905, but raised in Pass Christian, Mississippi after both parents died before she turned five. In 1928 she graduated from Tulane University with a degree in Design and was an editor for the girl’s college magazine. During this same period, her future husband True W. Robinson (the W. was for William), was studying Science at CalTech, where he graduated in 1929. He was from San Diego.

According to the eldest of their three sons, they met on a boat traveling from New England to New Orleans. He noticed her “in a deck chair reading an advanced book of philosophy” and “offered her a banana which had been in his pocket a little too long”. They married on July 4th , 1931. The wedding was on a weekend in Biloxi, Mississippi, so I think it’s safe to assume the day was fairly humid. By 1939, Adele was teaching Art at Wellesley College as Adele de la Barre Robinson, and in 1941, armed with a new MS degree, she became an Assistant Professor of Art. Meanwhile, over at Harvard, True Robinson was studying for a Doctorate in Pathology. Then, from around 1942 until at least 1947, he was an Associate of Zoology at the University of Illinois in Chicago. Somewhere in this time period he also managed to add Physiologist to his title. Eventually the couple settled in Birmingham, Alabama, possibly because of his job, and possibly because of its closer proximity to her hometown in Mississippi. True worked with medical schools in Birmingham. But his main claim to fame is that in 1961 he and Southern Bell Labs announced a partnership that allowed heart electrocardiograms to be transmitted live via telephone to an oscillograph machine at a distant location. In other words, he became AN INVENTOR.

At this point, you might wonder how on earth an Art Design major, debate team, Drama Club member ended up marrying a microbiology and technical geek, but get this: — in 1923, as eighteen year old teenagers still living at home with their parents, they were BOTH licensed Amateur HAM radio operators!

While True was busy studying and inventing, Adele kept busy creatively. In 1949 she published a booklet of selected verse titled, Summer’s Lease. And when they moved to Alabama she became an Assistant Professor of Art at Howard College (now Samford University), while True also taught at the school. In 1959, students performed a play she wrote titled “Birthday in Venice”. More importantly, by 1955 she was friendly with the local female State Arts Chairman. This is most likely why, in 1963, the Birmingham Festival of the Arts sponsored a booklet called The TOKEN. It was Adele’s first recognized foray into publishing other writers. I should probably remind you now that The TOKEN is the booklet my father tossed onto my lap back at the beginning of this story.

Sometime before 1965, Adele and Charlotte Kelly Gafford, a poet and teacher from the English Dept. at UAB, began producing quarterly issues of a highly regarded magazine titled FOLIO. The content included poetry, short stories, undergraduate writings, and occasional graphic art. Many of the issues had poems by my father near the front. By 1968 Charlotte had accepted a teaching position in Vermont and moved there. On her own, Adele ran the magazine for a while and then Myra Ward Johnson joined her as co-editor. In 2015 I had a telephone conversation with Myra and she commented, “We always got excited when your father sent us poems!” Initially a quarterly magazine, FOLIO later settled into a semi-annual production schedule.

For his part, my father introduced FOLIO to his circle of friends and helped its reputation spread around the poetry world of Manhattan. An issue from 1968 contains a poem by his friend Elizabeth Lambert and graphic art from Umaña. Elizabeth was married to Cesar Ortiz-Tinoco, who later became the subject of my father’s poem “What’s That You Say Cesar?” Umaña was a 1964 collaborator with my father for a publication titled “LINES/POEMS”. His wife, Helen Mcgehee, was a lead dancer with the Martha Graham Company and friends with my stepmom.

Adele managed to keep FOLIO going for 10 volumes consisting of two or more issues per year. I think she would be pleased to know that copies of the magazine are now sold as a cherished commodity on auction sites. It was never a money making venture, and Adele’s husband was the primary financial backer. As far as I can tell, the final issue of FOLIO was in 1974.

In 1979 Adele passed away at the age of 72, and the world became that much less creative. Recently I asked my stepmom if she knew why Adele died at such a relatively young age. I must admit, I was surprised at the answer. “Alzheimer’s Disease; it was very sad”.

A vague feeling of loss settled over me initially, but this was gradually followed by a sense of peace that comes from solving a puzzle. I realized that I now had the key to a deeper understanding of the poem.

The poets Adele helped launch and nurture continued to grow in stature, expand their network, and even teach upcoming poets. That is a legacy worth having. I think she would have been incredibly proud to learn that my father eventually became the Poet Laureate of Alabama. After all, she had an early hand in putting him on that path. And clearly he realized it and was grateful.

(Left) FOLIO cover. Each issue was the same design, but with different colors.

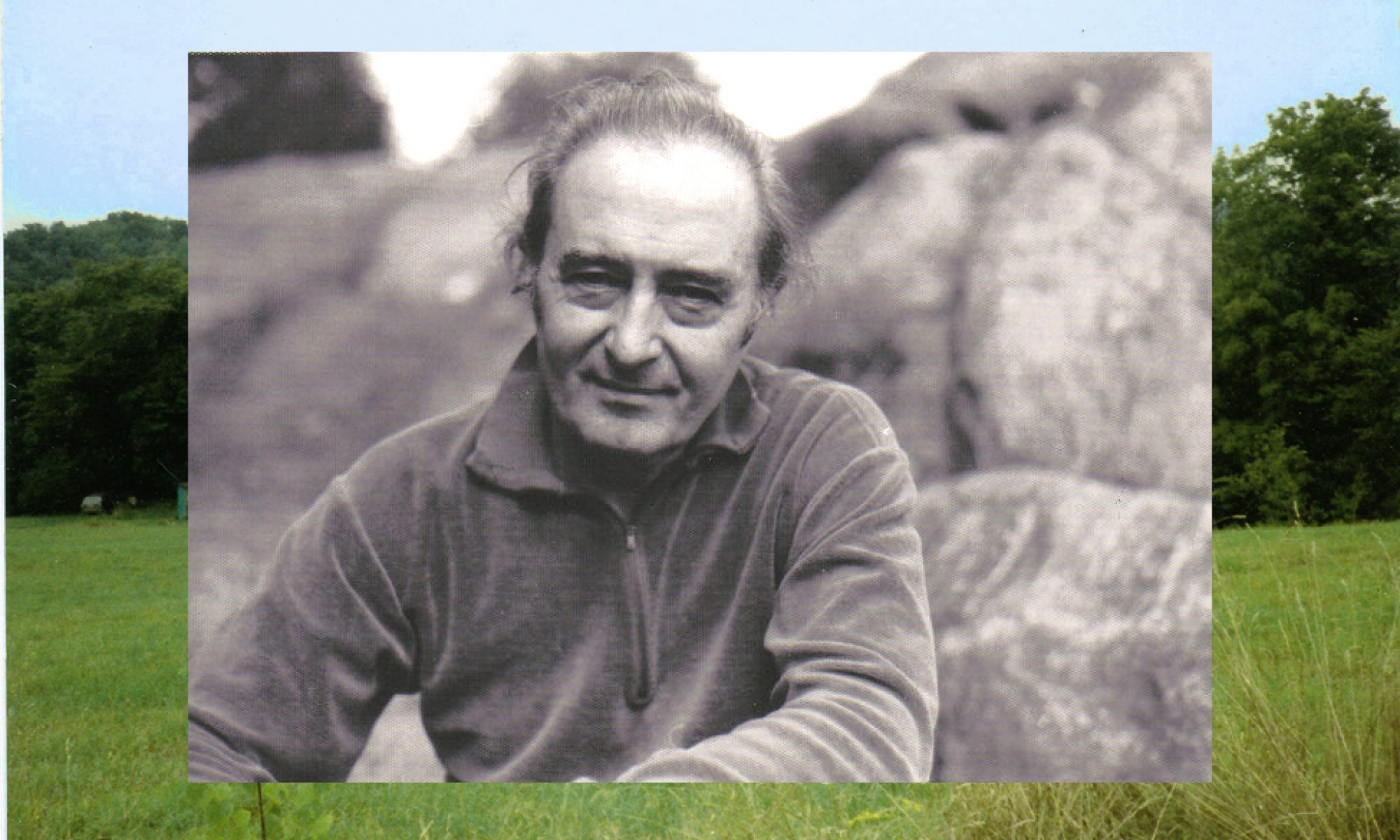

(Right) Adele Sophie de la Barre Robinson, at the age of 22. Senior year photo from the 1928 Tulane yearbook. Born May 27, 1905 — Died Jan. 30, 1979.

—E. Glaze

I am searching for family history and what you have done here is wonderful and precious to me.

This is Peter Rodes Robinson, first son of Adele and True Robinson. I was born on Christmas Day in 1942 at Randolph Field in San Antonio, Texas.

Next came Barry Scott Robinson (alive and well in Birmingham) and then Nicholas Bailey Robinson who drowned at Lake Martin at age 20. I have wondered if this tragic event triggered Adele’s Alzheimer’s disease.

The spring of 1970 after Nick died Adele was talking with me and my young wife Judy. She said, “It’s spring, everything is returning to life. I keep thinking, surely he will come now.”

Later I wrote this haiku:

Past dogwood white

She watches with new hope

For her dead son

I live in the Dominican Republic now. I have one son, Clayton Bailey Robinson.

Some more facts.

Adele was born in White Castle, LA to Nelson Edouard De La Barre and Daisy Bailey of Pass Christian, Miss. Her father died before she was born and her mother died before she was five. A very hard beginning for a remarkable lady.

After CalTech True started a PhD. program at Harvard. Adele was at Wellesley, but they met on a boat going from New England to New Orleans. He found her in a deck chair reading an advanced book of philosophy. He offered her a banana which had been in his pocket a little too long.

Adele had trouble conceiving. It was a scientific friend of True’s who provided the supplemental hormones which enabled Adele to give birth to me in the middle of WW II. She was 37 then.

By 1947 our little family had settled in Yellow Springs, Ohio. True was still in the military working at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. Barry and Nicky were born there.

We moved from Yellow Springs, Ohio to Birmingham in January of 1950. True had taken a position teaching physiology at the Medical School of Alabama.

We moved to 2 Montcrest Road in Crestline. Adele felt like expensive and snooty Mountain Brook was not the best fit for our educated and cosmopolitan family. She scouted homes in Forest Park and in the summer of 1955 we moved to 4167 Cliff Road. It was a wonderful large home with a patch of woods included in the lot going up towards Altamont Road.

Before the Token there was a mimeographed publication called the “Off-Off”. Adele was referencing Off-Broadway. Not even on Off-Broadway but “off-off”!

Barry and I have two complete sets of the Folio. I’ve often thought I should do the work to make them visible on the internet.

“It seems likely that Adele and her husband financed it.” Yes. Adele was very grateful to True for this. She saw him as a patron of the arts.

Adele sold some subscriptions, mostly to libraries all over the US.

Being with my mother as she slowly succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease was very sad. They called it “organic brain syndrome” in those days. Of course I thought there would be a cure. A sad realization for me that there are limits to what science and medicine could do.

One night in January 1979 True had an Air Force reserve meeting to go to, so he brought Adele by the house where I was living with friends on Crescent Drive. That evening she wet herself. I helped her take a bath and we found a nightgown for her. I thought it best to have her sleep there rather than go back out in the cold. True came by to get her after she was already in my king-size bed.

As we were going to sleep I started rubbing her forehead which she always enjoyed. Then she reached over and rubbed my forehead. I said, “We can still rub each other’s foreheads.” She responded “Yes!” very vigorously.

In the morning I made her scrambled eggs which she ate from a little wooden bowl. I never saw my mother alive again. Adele died a few days later.

LikeLike