A big foot bird

from the time we got him,

he was loud like an opera-singer ordering lunch.

Once delivered out of his hard-luck prison,

he’d slip in only when you weren’t watching, to eat,

and always,

surprising you in doorways

going the other way,

left your hair scattered in a thousand directions.

Bent in a skew-winged angle

before our breadbox,

he’d walk-around the bright reflection,

courting it with chuckles and screams.

And he battled among the birds of the stove

in the stainless steel pots

so they burnt him, and he yelled with fury.

Doting on butter, he stole it off our bread,

took his bath in the water

we were about to drink,

admired strangers greatly,

often coming on with furious hellos,

and explored stupefying mountain passes

of their heads and shoulders.

He would laugh at symptoms of cardiac arrest,

he thought they were little exciting earthquakes.

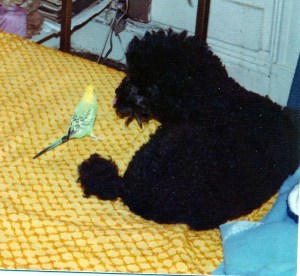

The dog would commence to shiver, seeing his coming,

watch with disciplined horror as he

paced up to his resting station,

and plucked out the hairs of his nose, one by one.

All of which makes his dying

seem as unaccountably absurd

as that of the dearest friend.

Was it only four years he came to stay?

We buried him under

the newly dead Philippine Orange,

adding a failure of knowledge and intention

onto another, hopefully.

What I really wanted to do

was to make a white-hot charcoal fire

inside the hibachi

set on the back fire-escape,

and send him up in the smoke fume

of a hero’s departure.

Verdi, I swear I’d have heard

your soul of a truck-driver

go up to freedom

passing the top of the sky coping

like a discovering squawk.

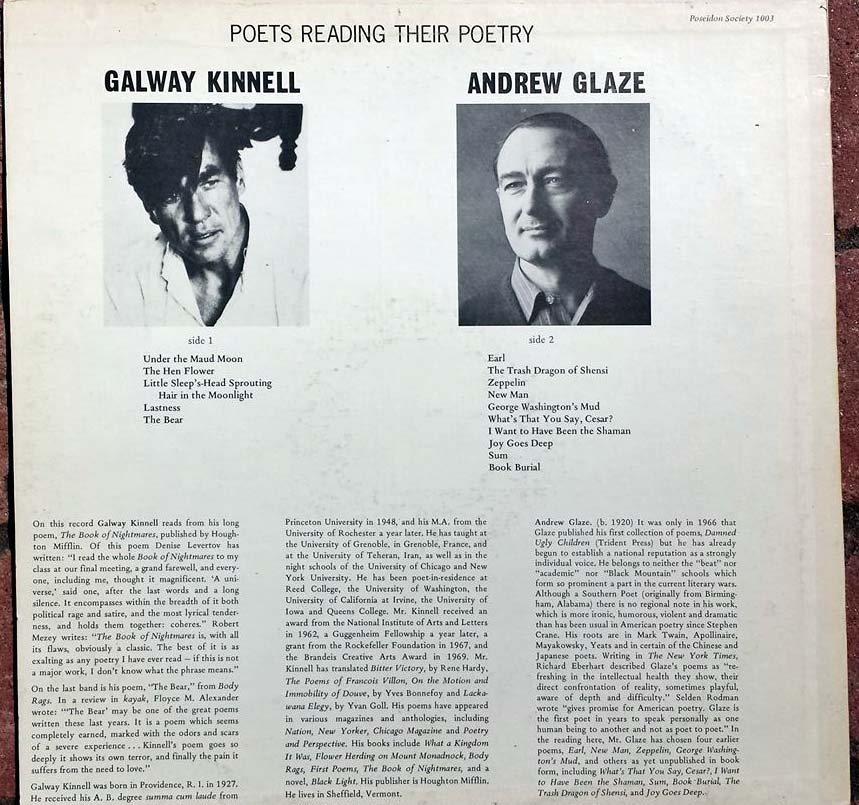

© Andrew Glaze 2023.

A previously unpublished poem, which was actually written back in the 1970’s.

The parakeets of my childhood were as follows:

Linda,

Bluie,

Bluie 2,

Tweeter,

Tweeter 2.

By the time we got a new parakeet in my teens, my father announced that HE was naming this one.

Linda, moved to NYC with us from Alabama. Bluie was the early subject of an unfortunate accident due to his love of walking on the floor, and Bluie 2 was a victim of neglect when my parents suddenly separated one summer while I was with relatives and my father wasn’t thinking clearly. Tweeter was an older bird from a classmate that we adopted, and I can’t remember what the story was with Tweeter 2.

Verdi was the first green parakeet we’d had since Linda, and had so much personality he stood above any dog, cat, or turtle we’d owned. Although I must admit that Frankie, the guinea pig that lived in our bathroom, was definitely an attention grabber. He’d lurk behind the toilet and come out to greet visitors after they sat down on it, much to their consternation.

Verdi was highly intelligent, fearless, always curious, and had the entire household in his claws. My father named him after the Italian composer, Giuseppe Verdi. That name, in English, is Joe Green, which actually seemed more appropriate to his personality.

Verdi had free range of our entire apartment, and that is saying a lot. We lived in what was referred to as a “railroad flat”, which meant that the rooms were laid out like railway cars running from the front of the building all the way to the back. Verdi could start off in the living-dining room space at the front, fly down a hall, pass through my parent’s room, continue past the bathroom, and reach the kitchen. He could have gone further and ended up in my small bedroom past the kitchen, but it held no interest for him and the door was always closed. It was on the fire escape outside my bedroom window, that we would sometimes use our small hibachi grill to cook a steak or two.

Because of the sheer length of our apartment, Verdi quickly realized that he could save a lot of effort if he simply hitched a ride on any of us headed in the right direction. Typically he’d pick a head or shoulder to travel on. If it was a shoulder with convenient earrings to investigate, all the better!. As a ballet student, I often wore my hair in a ballet bun on top of my head. For Verdi, it was an ideal seat for commuting. Sometimes, he’d hop off in my parent’s room, to grab a snack in his cage. Other times he’d choose the kitchen, although, if we passed the bathroom along the way, and the door had been accidently left open, he’d delightedly flit inside there instead. The bathroom medicine cabinet mirror was his favorite hangout. It was very difficult to get him to leave once he’d taken residence at the top and re-kindled his ongoing romance with the reflection in it. The billing, cooing, whistles, and chortles could go on for hours. This is why we tried to keep the doors shut.

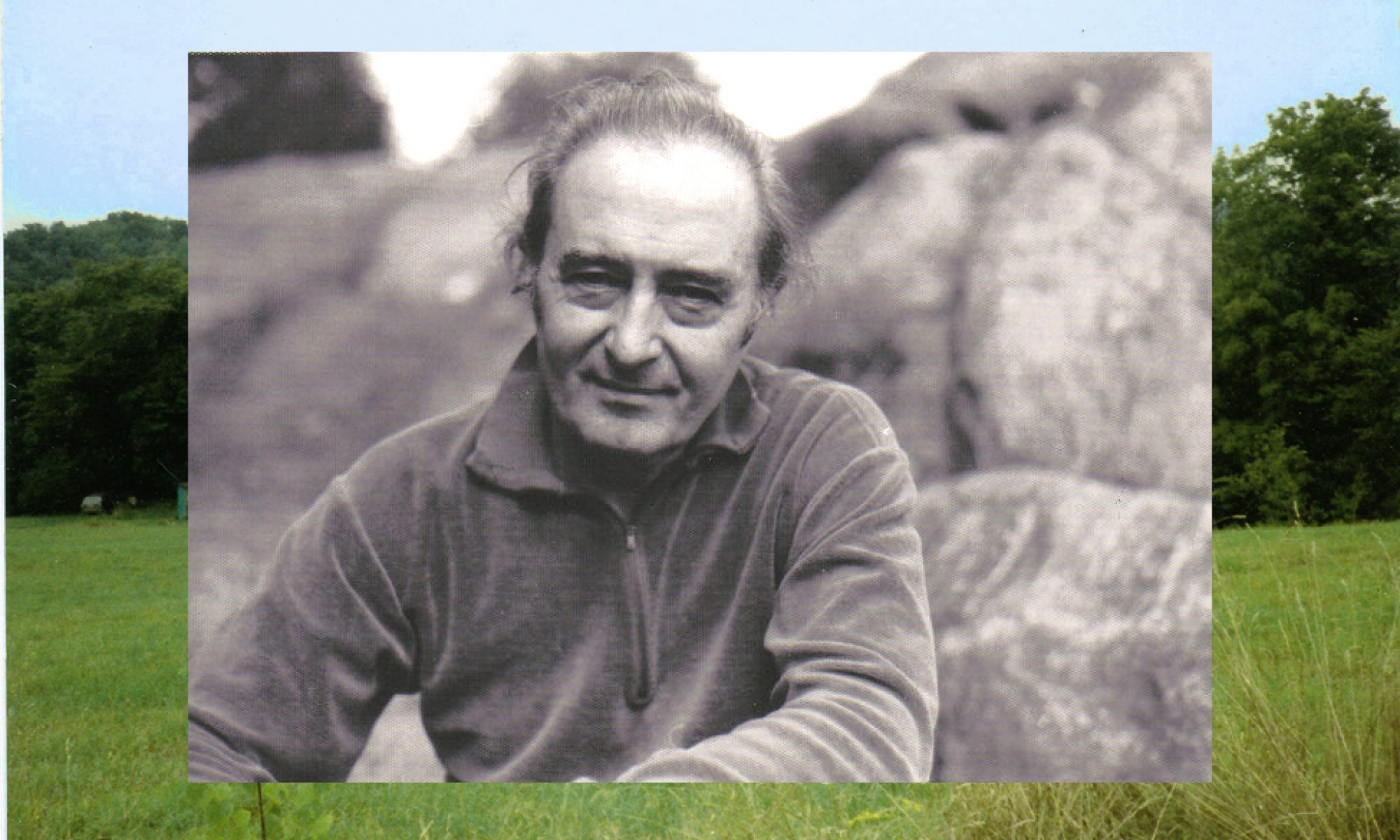

My brother remembers him spending a fair amount of time on my father’s head. The attraction was logical since my father’s fly away hair was feather like, particularly first thing in the morning when he resembled every stereotypical mad professor image I’ve seen.

As my father describes, Verdi also maintained a flirtation with the stainless steel reflection of the bread box, as well as the Revere ware pots and pans. But his most challenging relationship was with the bird reflected in my stepmom’s make up mirror. The mirror in question was a round one on a pedestal. She quickly realized she had to put her makeup on first, and THEN let Verdi out of his cage. Otherwise, they’d BOTH be trying to see themselves in the mirror. The caveat being that, because of the round shape of the mirror, and his clawed feet, Verdi would consistently start to slide sideways, and constantly have to clamber his way back up to the top with tiny side steps.

Verdi also stole her false eyelashes on a regular basis.

There was one occasion when a visiting friend of my parents brought his girlfriend along, and, as they all sat in the living room, Verdi decided to join in. The girlfriend turned out to be afraid of birds and panic ensued.

At night, we’d put him to bed for his own protection. This proved to be challenging. We either had to sneak up when he was in his cage eating, which was not an easy thing to do. Or, do an alternative that I came up with. We’d turn all of the lights out, knowing that he would not fly in the dark, and then point a lit flash light at the cage entrance. This worked 100% of the time. We also put a cover over his cage, otherwise, he’d wake up earlier than we did and let us all know about it.

The two of us had a little game we played together. He’d climb on my chest and I would open my mouth. With interest, he would poke his head in and begin inspecting my teeth, eventually he would reach for my tongue – which I would slowly begin to pull further and further back. At that point I would keep my teeth open, but gently close my lips while his head was inside my mouth, and he would pull his head back out and furiously berate me for playing a trick on him. Then we’d do exactly the same thing the very next day.

Verdi loved to give bird kisses, cheek nuzzles, and was very generous with all of us. He was much braver than our black mini poodle, Inky, and would brazenly walk right over to him when they both happened to be on the bed. It is also very true that Verdi loved butter, and would steal any he could get his beak into. But then I think he also enjoyed eggs and toast crumbs when left unguarded. Basically, he was a pirate in feathers.

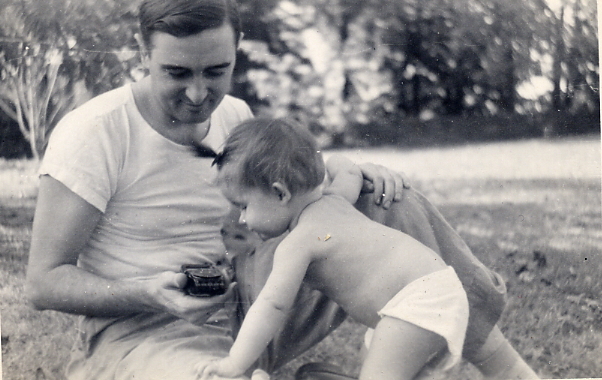

Recently, I’ve been sorting through books and papers that were my father’s. First, I came across an old book and noticed crayon squiggles on the inside of the cover, with little nibbles along the outer edges. I identify this as proof of my mother’s description of me, crawling beside a bookcase as a baby, pulling all the books out so I could scrawl in them, closely followed by her pet rabbit, who happily nibbled on books left in my wake.

Last month I came across a folder of older poems by my father, printed on older paper, with little beak bite nips all along the top edge of one page. I immediately recognized Verdi’s handiwork. He died in the early ‘70’s when I was living in Europe, and I cried when I got the news.

I was touched to discover that his signature still lives on.

I’m thinking about framing it.

—E. Glaze

Verdi preparing to disturb the pet poodle.

Verdi raiding somebodies breakfast

All photos are owned by the Andrew Glaze Estate.