As I walk mornings down Bleecker Street,

I meet ten saints with filthy demands.

The tenements shout with holiness,

God reels by or sleeps on the curb,

at home everywhere in the wrecks and bars,

in the stale tobacco and business,

and everything that’s wild and absurd,

like madness with madness and holding hands.

I had rather ten faces than ten birds,

I don’t sense deliverance in a tree.

There is no impossible in lakes,

there is more miracle in a crowd

than in a Rocky Mountain or me.

There is more holiness in an eye

than in a scroll of holy words.

God’s here, thank God, in the market place!

Viva the Signor of warts and turds!

© by Andrew Glaze, 2015, from Overheard In A Drugstore.

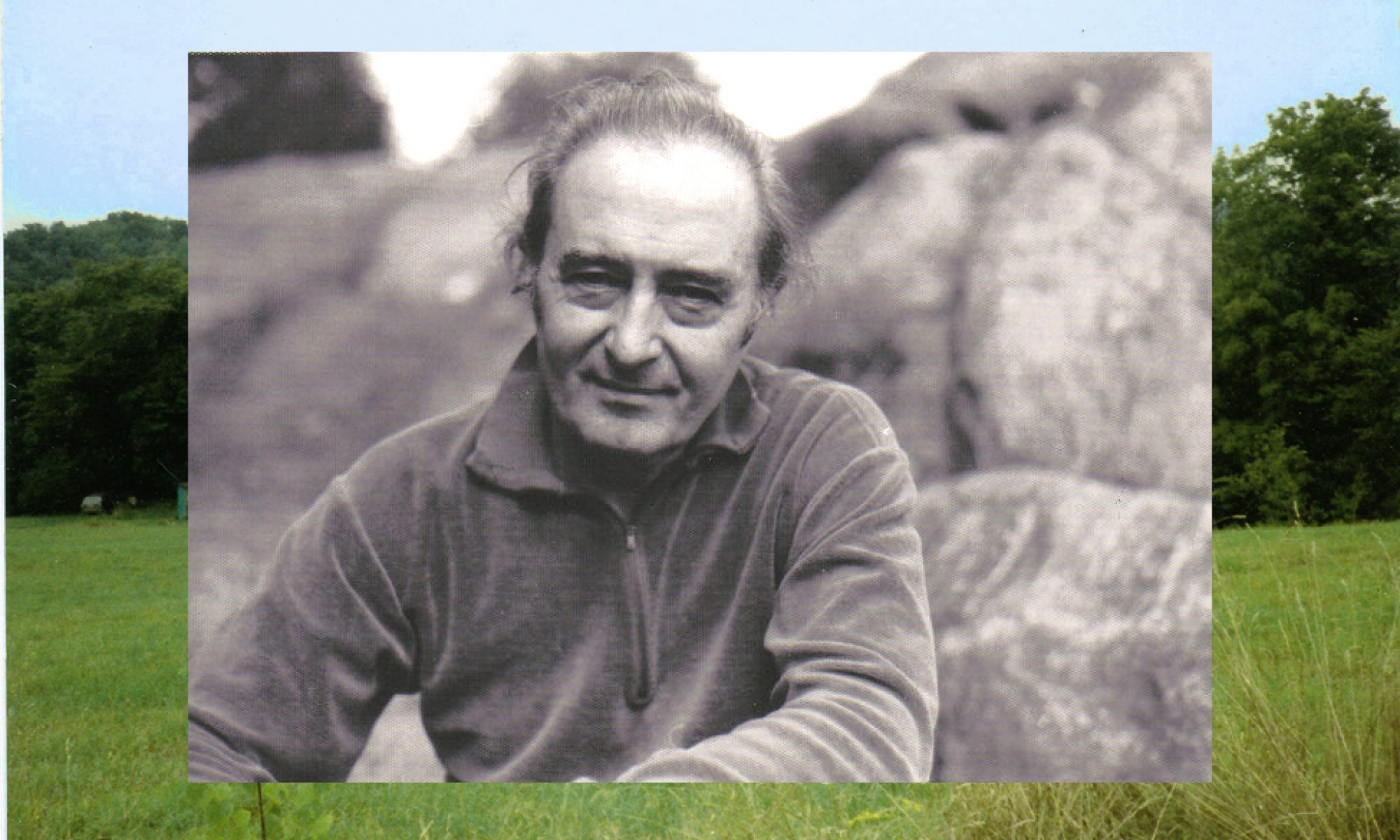

In 2008, Pulitzer prize winning poet Galway Kinnell sent my father a letter stating that he loved this poem, and would always remember the final line. They’d both taught at Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference within a year of each other, and would eventually appear on the A and B sides of a recording created by the wife of composer Alan Hovhaness. Betty Hovhaness was also from Birmingham and owned a record company called Poseidon Records. She’d created it primarily to promote her husband’s work, but decided to record my father reading poetry and asked him who he would suggest for the flip side. He recommended Galway Kinnell, and she agreed.

Many years later, when Kinnell died in October of 2014, my father kept a clipping of his New York Times obituary on the table beside his living room chair and grieved for several days afterwards. Besides the fact that he admired his work, I believe it’s because he was so proud of the fact that Kinnell really liked his poem.

The poem “Alleluia” was originally titled “As I walk mornings down Bleecker Street”, and it began to develop in the late 1950’s when we moved to Greenwich Village at 173 Bleecker Street, on the corner of Sullivan. “The Village” was vibrantly alive with creative arts in those days, but still had regular neighborhood stores. There was a laundromat at the bottom of our building, and a drugstore across the street.

It wasn’t until 1993 that I discovered my father’s brother in-law fondly referred to him as “The first beatnik of Alabama”. I have to admit, it was a surprisingly accurate description. Despite going off to work every day in a suit and bow tie, the mild mannered conventional exterior of my father hid an interior that longed for creative inspiration and supportive peers with similar goals. That first Christmas my father decided he wanted a guitar, my mother asked for bongo drums, and I was presented with a tambourine so I wouldn’t feel left out although I had absolutely no clue what to do with it. My mother also asked for oil paints and brushes. One day I came home from school and discovered she’d used them to create a swirly free form painting directly on a wall in our living room. As I’d been raised to NOT draw or paint on the walls, I remember being somewhat stunned. Clearly my parents were adapting to Greenwich Village artistic life a lot faster than I was. During this same time period, a block away from us at the Village Gate, Peter, Paul and Mary were performing on a regular basis, and nearby, at Washington Square Park, a pair of elderly mandolin players would entertain the strolling public pretty much every evening. By 1960, half a block away, the musical “The Fantasticks” would launch into the first of what would eventually become a 42 year run at the Sullivan Street Playhouse. I was attending the first and oldest progressive private school in Manhattan, on 12th street, and one of my classmates was the sole child of the late James Agee. In 1957, my schools mandatory dress code was denim jeans and tee shirts, and boys and girls did everything equally. It was my mother who pushed for this form of education. Oddly enough when I graduated and became a student at the High School of Music & Art, I went through a reverse rebellion and avoided jeans and slacks for four years.

Despite the fact that we lived in a bathtub in kitchen apartment, with a shared toilet in the hallway, life was pretty good, and certainly very interesting. One afternoon my father came home and told me that he’d spent some time writing at Café Figaro. It was one of no less than four cafes at the cross roads of Bleecker and MacDougal streets. Somehow he’d learned that it was a hub for writers and poets. He explained that the custom was to sit at a table while you worked on a written piece. When you felt you’d made progress you would simply stand up unannounced, read your work aloud, and sit back down again. I have no idea if anybody made comments, or “snaps”, but I’m fairly certain Alan Ginsburg was part of the scene at the time although my father never cared much for his poetry.

“Alleluia” is my father’s love letter to Greenwich Village and Manhattan, warts and all. Neither of my parents ever regretted leaving Alabama for Manhattan. My mother said she felt at home the moment our Greyhound bus first came across the George Washington Bridge, and NYC provided my father with the supportive poetry world that Birmingham lacked at the time. My father returned to Alabama 44 years later, and found a vastly improved poetry scene in Birmingham, but both of my parents continued to love Manhattan until the day they died.

—E. Glaze

“Thanks for the review that your friend managed to get to me. Thank you even more for your poem “Alleluia” which I found very moving from first line all the way to the last line. I will remember your closing line: “Viva the signor of warts and turds!” I hope you won’t let being eighty-eight stand in your way for more years of fruitful work. If I am ever in Alabama, I will look you up, provided you agree to do the same to me if you are ever in Vermont.”

Copyright of the Galway Kinnell Estate, property of the Andrew Glaze Estate.

Copyright of Poseidon Records.

Copyright of Poseidon Records.

The wall painting my mother did at our apartment on Bleecker Street. The photo is a bit faded, and the camera flash bulb is reflecting off of the rectangular shape. In real life the colors were much brighter, the object on the lower left was greener, and the rectangular box was deep blue with yellow. It was very 1950’s art style.

Property of the Andrew Glaze Estate.