Bending up the stairs,

dance case swung to my shoulder to the back,

I looked one flight above and saw Nijinsky

sitting on the steps—I swear—

his thighs wide-stretched and huge,

facing me with wild, high cheekbones, V-shaped chin,

clinging over me like an angry Scaramouch.

His eyes burned with a hollow light,

and stared in mine like a curious grievance brought to bay.

Contempt drew down the corners of his mouth,

made ploughed contours over the ridges of his eyes.

—you are too gross to speak of—he seemed to accuse

—old clot of fifty-eight,

desecrating my youthful art—.

“Exercise!” I stammered.

How could I make the ridiculous word compose itself?

I writhed in the contumely of his eyes

with their ghostly fire,

so the truth came hurtling out

like a series of tours de reins.

“I pickpocket a taste of it, that’s all—for love.”

His face cleared as though with a blast of light.

He grinned, fading,

and I swear, left a fleeting thought

as the stairs grew stairs again

and a tiny wind blew,

—Nothing excuses anything—nothing—

but passion’s the most forgivable greed in a thief—.

© Andrew Glaze,1991, from Reality Street

This was the first poem ever published by Dance Magazine, August,1980.

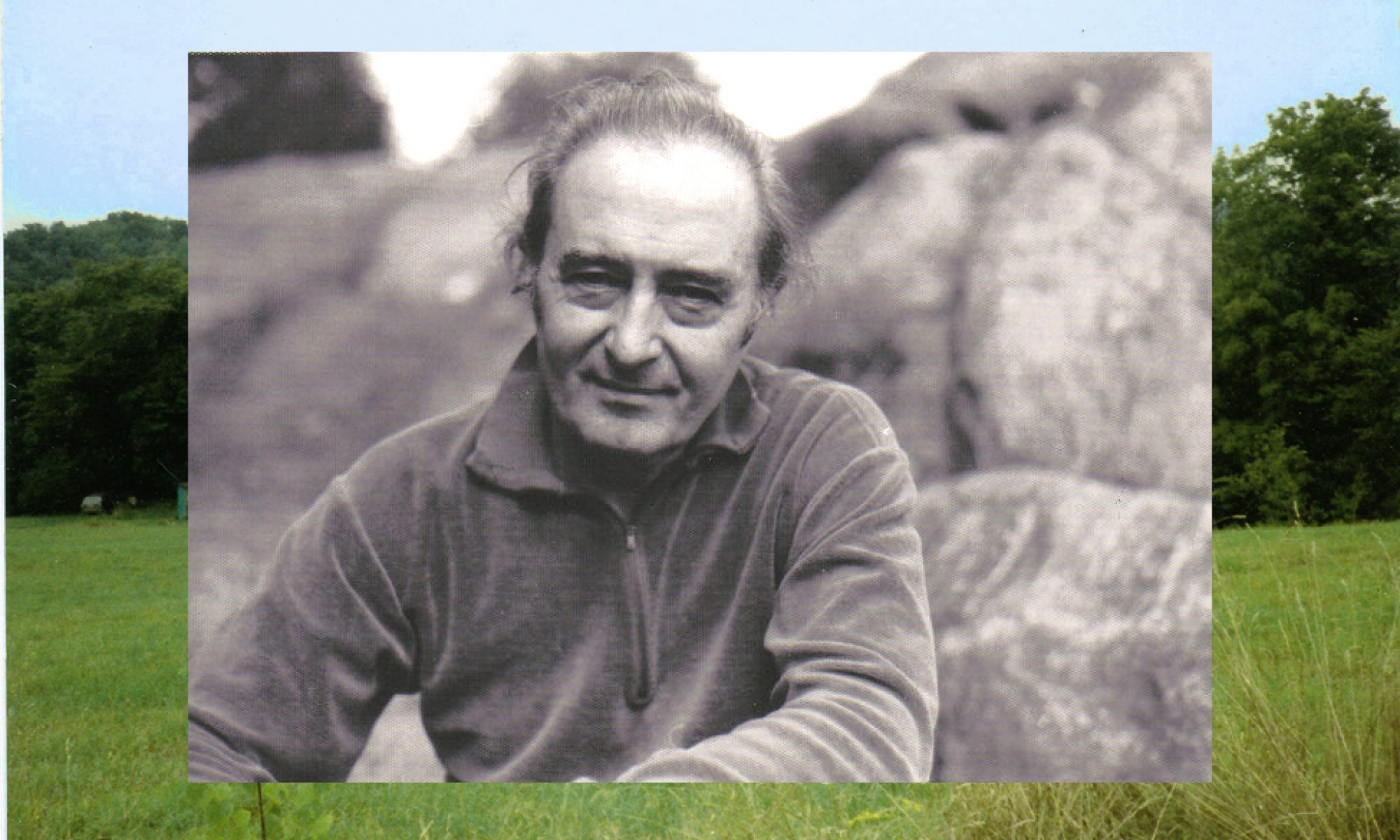

What made my father decide to start ballet lessons at the age of 45?

In his youth my father played soccer and softball at school, skied, hiked and biked in France after WW2, and played golf and tennis in his 20’s. When we lived in Greenwich Village I watched him hit tennis volleys against a designated brick wall at a local playground. After we moved uptown to 53rd Street, he biked to and from work every day, and occasionally rode around in Central Park.

I had been a ballet dancer since age 3. This was for two reasons.

One. My mother noticed that I spent large parts of the day dancing around the house.

Two. She happened to read Agnes De Mille’s best-selling autobiography.

In it De Mille revealed that she’d led a tortured life, because she’d been denied ballet lessons as a child. My mother said she looked at me pirouetting around the room, went into full panic mode, and quickly enrolled me in The Lola Mae Jones School of Ballet. This was Alabama, and, yes, not only was there a genuine “Lola Mae Jones”, but she had a daughter with the same name, so there were actually TWO of them. My excitement was short lived. Even at the age of 3, I was worldly wise enough to realize that pretending to be a clock or a teapot had little to do with ballet, and I craved the real stuff. By the time I was five I still wasn’t past the tea pot phase, and couldn’t handle another minute of pretending to be an elephant swinging my trunk. I retired.

THEN, we moved to Manhattan and my father’s cousin Hansel took me to see The New York City Ballet perform Balanchine’s version of The Nutcracker. I wanted to be one of the children in it, and by that spring I’d come out of retirement and auditioned for their school. By September I was a student at the School of American Ballet. My teapot days were over. Instead I had two Russian ballet teachers; one frequently terrorized us to tears, and the other was so sweet we took advantage of her. I soldiered on with determination.

However, my father’s own interest didn’t awaken until after he met and married my stepmom. She was also a ballet dancer. At that point, he wanted to learn more about the career of his new wife, share in her interests, and understand our terminology. In addition, he once told me that he took up ballet for exercise, because he found traditional calisthenics to be extremely boring. I suspect it also appealed to his lifelong love of classical music, and he enjoyed the easy comradery of his adult classmates. For me, the drawback was that my adoring father transitioned into a dad who not only knew when I was dancing well, but also knew when I wasn’t.

After he retired from his job in the 1980’s, he took up golf again, although his equipment was fairly ancient. I have it on the best of authority (my husband) that when things weren’t going well on the golf course (which was frequently), my normally mild mannered father would release a fountain of profanity that made other golfers blush. When it was really bad, clubs would go flying. This was not the case when he was at the dance studio.

He never flattered himself that he was very good at ballet, and truthfully, he was not. But he enjoyed it, and kept it up until he was 82. At that point he moved back to Birmingham with my stepmom, and switched to yoga classes instead. He kept up with yoga until he was around 93.

Personally, I think Nijinsky would have been rather impressed with that.

![]()

Vaslav Nijinsky, as the Golden Slave in Scheherazade, 1888.

—E. Glaze

Great!! This brings back so many memories and tears.

LikeLike