The beautiful is always bizarre–-Baudelaire

I tell you, David,

poetry ought to be shocking,

and poets ought to be dangerous people.

In whatever country, honest feeling is always

shocking and dangerous.

Anyone true to the heart can simply enough and at

any time be both.

But for their contempt we’ve ourselves to blame.

We’ve been cowardly.

We’ve made the stuff so cheap

begging their love

that poets are poor people

from wearing out the money of never was

passing it back and forth among themselves.

Rub the truth in their faces!

What is the point of being a poet, anyway,

if you can’t be a kind of prophet?

Hold their nose to the stink,

Say “look, this is it!

We are here by ourselves,”

say “there’s no kind uncle,

you will have to furnish the kindnesses out of your

own pocket.

If you see that, nothing can hurt you!

Stop kissing essences. Learn to respect

your essential rumpy importance.

And for God’s sake, don’t mistake my words for food,

when they’re nothing but spoons.”

Say with whatever gestures are customarily indecent

and the wildest possible musical accompaniment

“The sky will not move

for buckets of moonlight and French quotations.”

While they’re watching you chant like a demon priest,

kick away all those roses covering the cesspool.

How else make clear

that if there’s a reason

we bawl these songs to ourselves

as we push this stone to nowhere

for no apparent reason,

the reason is too simple to be believed–

like the snake swallowing his tail.

That music is useless,

That music is to eat and to make love and to make music,

one’s own music.

That music is music.

Why, this alone, if they could understand it,

would overturn all their systems.

Shout something simple and sensible.

For instance, that nothing done in boredom

is a human accomplishment.

They’ll think you’re talking about leisure

or the family cookout. Make it clear you’re not.

Don’t worry. If you brandish it seriously or humorously

and go ahead and shout it in the street,

they’ll only mistake you for an arsonist or a communist.

And smelling out the truth with their fear,

roll you in the garbage to comfort their taught lies.

You have to understand them.

They’ve only this one poor fence against accepting the nature

of themselves

and they truly fear it.

They’ll never suspect you’re a poet.

They cannot allow you a worthwhile reason

to deserve to be punished.

So they won’t punish you for the right reason.

When you speak of love,

they’ll try to pretend you mean Cleopatra

or some other anal-vaginal queen.

And only two or three will dare recognize

your corrosive subversity.

Make sure they have to make fools of themselves

to ignore the difference.

Are you afraid?

If you’re not, there’s something wrong with you!

To tell them what they care for most

is as relevant to their souls

as the sugar level of the urine of pregnant beetles?

But you ought to be more afraid of dying without

having tried!

What is important except to be what you are?

Make them call out the cops if possible.

Poetry had better be shocking or shut up.

What earthly good to say

that Spring will be around again next year ?

© by Andrew Glaze, 1963, from Damned Ugly Children.

ABOUT DAVID MATZKE:

The first time I met David Matzke he was called “Jeff Crawford”, had a wife named Connie, a young son, and I was 7 years old. In 2006, my mother reminded me that Jeff and Connie originally came into our lives through her.

In 1957, our first true apartment in Manhattan was the ground floor rear garden flat of a brownstone on 102nd Street. We were half a block from Riverside Drive. I had the only bedroom as well as direct access to the backyard. A friendly artistic black couple named Oscar and Zizi lived directly above us. After years of trying to treat blacks in the South as equals, only to find that the blacks were terrified to accept the invitation for fear of outside retribution, my parents were ecstatic to be able to freely strike up a friendship.

On weekdays, my father took the subway to work at British Tourist Authority after dropping me off at school in Greenwich Village, and my mother was the Superintendent of our building. In exchange for using the repair and maintenance skills she’d learned while she and my father renovated our house in Birmingham, we had free rent. Very early in their marriage my mother said she’d complained “You get to do all the fun stuff”, because cooking, cleaning, and laundry never held much interest for her. He listened, and they agreed to split the jobs between them. Years later, she taught me how to dry wall and helped me renovate parts of my home. Most memorably, in 1989, when she decided I needed to learn how to change the oil of my car, she placed a huge piece of cardboard on the ground under the engine, gracefully slid on her back to get to the oil tank, and began to demonstrate. All while wearing a pale pink pencil skirt suit, stockings, and high heels. My father became the person who dragged me off to buy good hairbrushes, to the dermatologist for my skin, and made sure I was brushing my teeth regularly. But I digress…

Every evening, after my father came home, my mother would head off to her second job as a chorus girl. She was performing in an off-Broadway comedy spoof called, “Best of Burlesque”. TV comedian Tom Poston was the headliner, and retired burlesque stripper Sherry Britton was the narrator. My mother was one of “Nelle’s Belles” and with great delight the producers gave her the stage name “Sugar Glaze”. “Lilly White” was another cast member. Nelle Fisher, the only dancer on the Captain Kangaroo TV Show, was the choreographer. For years, Nel taught movement/dance lessons in the studio building attached to Carnegie Hall. I remember sitting and watching my mother in one of her group classes during this time. After that, whenever the Dancing Grandfather Clock appeared on Captain Kangaroo, I knew it was Nelle Fisher.

Every weekend my mother would bring her evening job costume home to hand wash and hang it up to dry. It was a sort of flesh colored leotard with a poufy tutu ruffle around the hips and butt, a bra sewn inside, many sequins, and white elastic shoulder straps that had been dyed with facial foundation makeup to make them blend in with skin tones. I was fascinated.

There is a 2008 New York Times obituary for Sherry Britton that states, “Ms. Britton was the onstage narrator of “Best of Burlesque”, a two-hour show at the Carnegie Hall Playhouse, which also starred an eye-rolling Tom Poston as the top banana, or star comedian. With poker-faced chorus girls singing off-key and rhythmically chewing gum, the show spoofed what was by then a lost art form.”

Yes, I can proudly state that my mother was one of those poker faced, rhythmically gum chewing, off key singing and dancing girls. In 2004, when she came across an out of print encyclopedia of Broadway and Off-Broadways Shows, she showed it to me, gleefully pointed out the name “Sugar Glaze” in the list of performers, and burst out laughing.

It was during the run of “Best of Burlesque” that Jeff Crawford’s wife, Connie, became friends with my mother. Connie was one of the wardrobe ladies. When we moved to Greenwich Village a year later, my father met Connie and her husband Jeff. They were both contemporary art painters. Interestingly, my mother later said she’d always felt that Connie was the more talented of the two. However, she never saw any of Jeff’s later work. Somehow my father and Jeff struck up a friendship.

In the ensuing years, my parents divorced, my father remarried, and we moved to 9th Avenue and 53rd Street on the West Side of Manhattan. We were near the Broadway Theater District and Lincoln Center. Then one day my father came home from work and told me he’d bumped into Jeff …except that Jeff was now “David Matzke”. It seemed that he’d used the name Jeff Crawford to avoid jail, but eventually had been tracked down and sent to serve a prison term in upstate New York. Now he was out, back in Manhattan, back with Connie, had a second son, and they lived around the corner from us. At some point, I remember my father explaining that David had become addicted to codeine cough syrup, and had broken into a home, or possibly multiple homes, to search the bathroom medicine cabinet.

Since I was an art major at the High School of Music & Art, in an effort to help them financially my father asked Connie to give me oil painting lessons for a while and David built me a wooden easel. The close proximity brought David to our house regularly. At times he’d visit for long therapeutic talks with my father, and I’d find them ensconced in our living room. On other days he’d bring paintings. Our 9th Avenue and 53rd Street apartment was what is described as a “railroad flat”. This is because it was the length of the entire building and you had to walk through every single room to get to the very front end or the very back end, just like you do on a train. As a result, we had loads of blank wall space, which David did not. And so for the entire duration of the 1960’s our apartment became an ever changing art gallery of David’s paintings. He’d hang them to dry and then come to replace them with new ones. To this day, the smell of oil paint and linseed oil immediately takes me back to 803 9th Avenue, at 53rd Street. It was a win-win situation. We had constantly changing art and he had a safe showplace.

Then one day David screwed up and everything fell apart.

It all started because my father bumped into Zizi, our artistic black female friend from our days living on 102nd Street. It turned out that she’d also moved into our neighborhood! So he invited her over, and David stopped by while she was visiting and was introduced. I remember arriving home from school that day and greeting them both. The problem was that Zizi and David continued the acquaintanceship and ended up having an affair. When his wife Connie found out she kicked David out. It’s hard to remember all the details now, but I’m pretty sure I remember a half-hearted suicide attempt – it may or may not have been Connie, something about a child falling off a fire escape from a lower floor, and an eviction notice, but that wasn’t even the full extent of it. What I do remember is relating a lengthy dramatic saga to my best friend at school and closing with, “If anybody had brought a movie script like this to a Hollywood producer, they’d have said it’s too unrealistic.”

So David left the city, and returned to his birth state of California. It proved to be an artistic rebirth for him. He eventually came back to Manhattan producing paintings in a new style with vibrant colors; a result of mixing his own paint and painting in the California sun. We still have one of his paintings from this period. It’s called “Fire Birds”. My personal favorite was a painting with blue flowers that an acquaintance of my father’s purchased.

I’ve always remembered something my father once related to me. He said that David had vivid memories of being a baby, and young child, who was obsessed with painting his crib mattress and walls. It was a constant issue and struggle with his parents, because, lacking any other medium to use, the only “paints” available were his own feces. Clearly, David was born to be an artist from day one. It was in every fiber of his being.

Somehow around this time, David met his next wife, Lisa, whom we all liked very much. Young, but with an old soul, she was a lovely person. They lived in Brooklyn Heights at the time and stayed in touch with us. I remember sitting on the fire escape just outside their kitchen window one evening and enjoying chatting with her brother when he visited from their hometown of Charleston, SC.

Unfortunately and tragically, when David & Lisa’s first child was born, he had cancer at birth and died not long afterwards. The shock sent them both into a spiral of depression, they parted for a period of time, and Lisa returned to Charleston. After awhile, David joined her there and they eventually had two daughters. David moved to New Orleans when they agreed to separate at a later point, but they reunited again in 1977 and had a son while living in Louisiana.

In 1981 David died in a mysterious fashion. His family tells me that he went off on a motorcycle ride to cool off after a heated argument with Lisa, and never returned. It was two years before they discovered what had happened to him. in 1983, the police found his remains in a wooded area on the other side of a nearby lake and used dental records and his wallet to identify him. Piecing the evidence together they concluded that his high blood pressure must have caused some sort of heart issue, he didn’t have his medication with him, and he died after dragging himself off the road. His daughter tells me that Lisa always felt in her heart that he must have died, and felt certain that he would never have willingly abandoned them. In 1983 Lisa called my father and stepmom to tell them the news.

ABOUT THE POEM:

The poem proved to be a problem child, not unlike the title subject.

In 1964, if anybody had predicted the future and warned my mild mannered, non-confrontational, kind, witty, intellectual, and bow tie wearing father, that this one single poem would create a firestorm of problems for him that would linger for years afterwards, I believe he might have reconsidered publishing it at all, much less in his very first book. Although he did later say it was one of the best poems in the book, in his opinion. The original version was actually titled, “To Jeff Crawford” and first appeared in a small Alabama published poetry booklet titled The Token.

The poem immediately attracted reviewer’s attention, and they either hailed or hated it. William Packard, a publisher and a professor at New York University, loved it so much he used it as an example in his teaching textbook The Poet’s Dictionary: a handbook of prosody and poetic devices.

On the “Hater” side, fifteen years later in 1979, Harvey Curtis Webster still held a grudge when he reviewed The Trash Dragon of Shensi for Poetry Magazine. My father referred to this in 1985 during an interview with Steven Ford Brown.

“Brown: You once remarked that a poem from that volume, “A Letter To David Matzke” was quite misunderstood by most people. And that it still got you into trouble?

Glaze: “A Letter To David Matzke” was like a red flag to a bull to a lot of literary types, and to a lot of the literary movement, apparently because of its naïve calls for “honesty”. In that wing of poetry which believes most strongly in artifice, craft, technique, indirect allusion, tradition and various theories of semi-mystical inspiration or hermetic art, it was regarded as a rude and sophomoric Jeremiad. As recently as four years ago, I got a review in Poetry which totally ignored the book ostensibly under consideration (Trash Dragon) and made a violent attack on this poem. All of which is pathetic, since I’d written the piece as an aesthetic guide for no one except myself. I never even had the intention of stepping on anyone’s toes. The piece has been considered an apolgia for “beat” poetry, “confessional” work, overtly sexual content, and heaven knows what else. Things which did not interest me at all. Most readers who objected, got angry so quickly they didn’t read much past “Poetry had better shock or shut up”. Sense went out the window. Some reviewer mocked poetry with such pretensions which lacked incest, homosexuality or rape to keep it honest. It makes one wonder what poetry is to a lot of people. Something pretty petty, which deserves whatever death it chooses for itself.”

My father later revealed the full extent of his subsequent ostracism, and how he came to understand the source, in an email. The recipient was poet and writer Steven Conkle, a friend and fan.

“Dear Steve:

Now that’s what I would call thoughtful. EPOS! I don’t know when they went out of business, but it must have been decades. And I was relieved to find that I could still read the poems without wincing. (Referring to poems of his in the EPOS anthology.) Let me see. That was after my first book, and just before Tony Rudolf in London broke his own rule and printed something that wasn’t a translation.” (Referring to his poetry booklet “A Masque of Surgery”.)

“I was getting discouraged about ever getting a second book despite 30 or 40 great reviews.

I never discovered why till I went to a lecture in the village (NYC), and Richard Howard was introducing whoever it was. At the intermission he came up to me, which puzzled me, because I’d never met him. He said, “Sir, when I chair an event like this I always pick an intelligent face in the audience to talk to. In this case it was you. Do you mind my asking who you are?”

I replied “My name is Andrew Glaze”. His face flooded with astonishment, “You’re Andrew Glaze!” he said, then with a kind of horror “YOU’RE ANDREW GLAZE“! He backed away and avoided being anywhere near after that!

That was my introduction to how the poetic establishment operates underground and covertly to try to force people to write as they wish.”

(He then went on to mention additional names as part of a tightly knit “clique”.)

Lacking acceptance into the poetry equivalent of “The old boys club”, he determinedly forged ahead and managed to find his own path to publishers, magazines, and fans to share his poetry with.

Currently, what amazes me is the fact that, despite the obstacles he overcame to get his work published, and a very long bibliography of known published work, I still continue to discover new entries to add to it! Clearly, given a choice between writing and record keeping, my father always picked the former. In a poetic sense, it appears that I’ll be spending time with my father for many years to come as I search across the web and his papers for signs of further publications. Luckily, I don’t mind; along with Poet Laureates, I have librarian DNA in me. I tend to enjoy the challenge of the search.

“Firebirds” by David Matzke (as seen from below). Property of the Andrew Glaze Estate.

One of David’s paintings is on the wall to the right. Others are on the left and down the hallway beyond. The photo makes the painting look dark, but in reality it was not. I always thought of it as “The Chair”. Photo property of The Andrew Glaze Estate.

The same chair painting is in the photo of me in 1966.

Two more of David’s paintings are on the walls in the photos below.

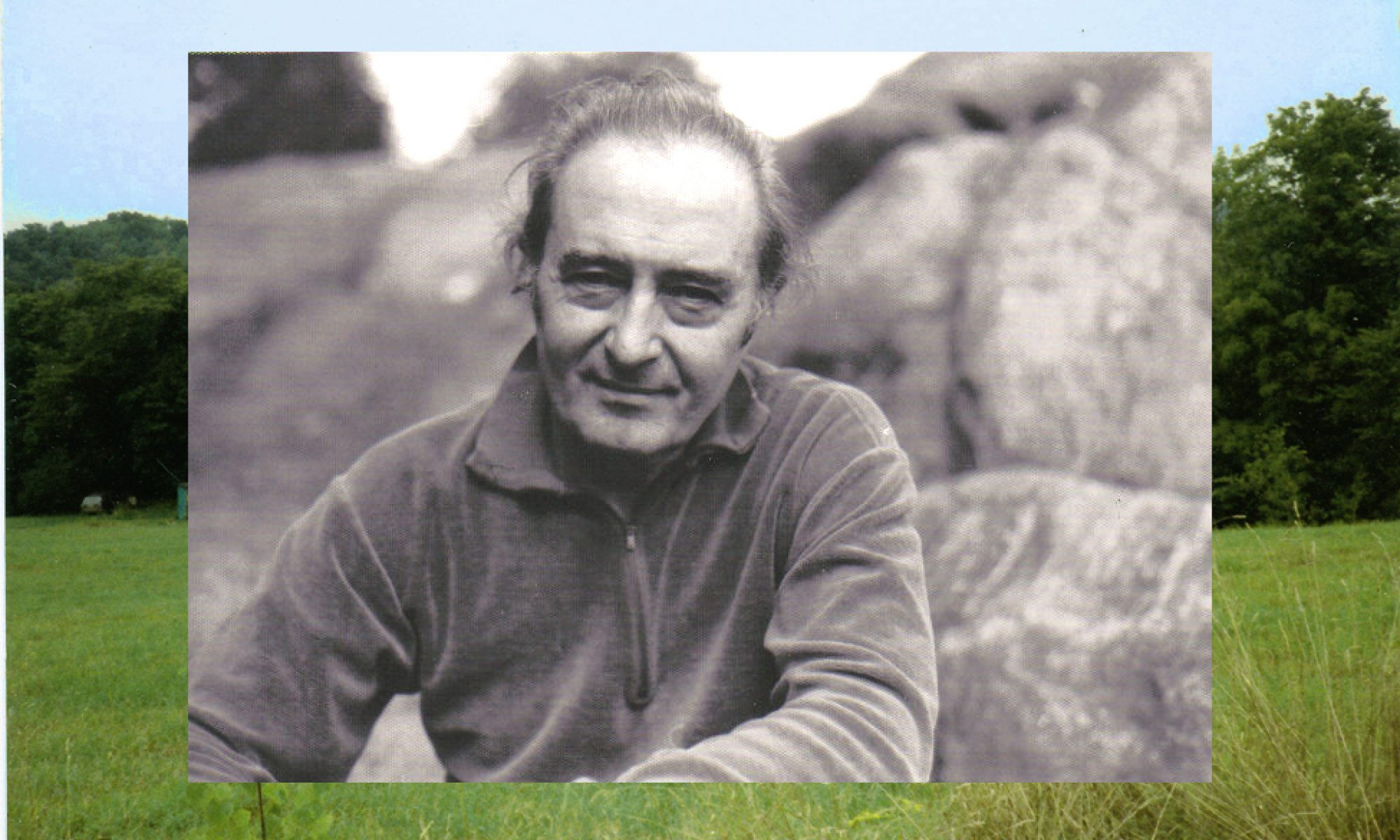

David Matzke 1929 – 1983

Original Cast Album cover, “Best of Burlesque”, 1958.

Dorothy Elliott (Glaze) Shari. These professional theatrical “Head Shots” were made around the time of “Best of Burlesque”.

— E. Glaze

Copyright of Poseidon Records.

Copyright of Poseidon Records.